Centrifugation is a widely used technique in laboratories and industries for separating components of mixtures based on their density differences. It plays a critical role in fields such as biochemistry, molecular biology, and chemical engineering, where efficient separation is often essential. Despite its simplicity in principle, the effectiveness of centrifugation is influenced by multiple factors that can significantly alter results. This article explores why these factors matter and provides a detailed discussion of the key parameters that affect centrifugal effects.

Why Certain Factors Can Impact Centrifugal Effects

Centrifugation relies on the equilibrium between centrifugal force and resistance governing particle motion. Centrifugal force (relative centrifugal force, RCF) is proportional to particle mass, rotational radius, and the square of angular velocity (Formula: RCF = 1.118×10⁻⁵ × r × (RPM)²). Insufficient RCF fails to overcome medium resistance, leading to incomplete sedimentation, while excessive force risks damaging particles or equipment. Additionally, sample properties (e.g., density differences, viscosity) determine sedimentation rates, and temperature fluctuations may indirectly alter outcomes by affecting medium viscosity or biomolecule stability. Understanding these intricate relationships is crucial for achieving desired separation outcomes.

Factors Affecting Centrifugal Effects

Rotational Speed (RPM/RCF)

Rotational speed is one of the most critical factors influencing centrifugal effects. It determines the centrifugal force applied to the sample. Speed is often measured as revolutions per minute (RPM) or relative centrifugal force (RCF), which accounts for the rotor radius.

Rotational speed directly determines RCF. For example, a rotor radius of 10 cm at 3,000 RPM generates ~1,006g RCF, while 10,000 RPM yields ~11,180g. High RCF is essential for small particles (e.g., viruses) or low-density-contrast samples, whereas low-speed centrifugation preserves fragile structures like cells. Case studies show mitochondrial isolation typically requires >10,000g, whereas erythrocyte sedimentation needs only 200–400g.

Considerations: Excessively high speeds can cause sample degradation or rotor damage, making it crucial to balance speed with sample and equipment limitations.

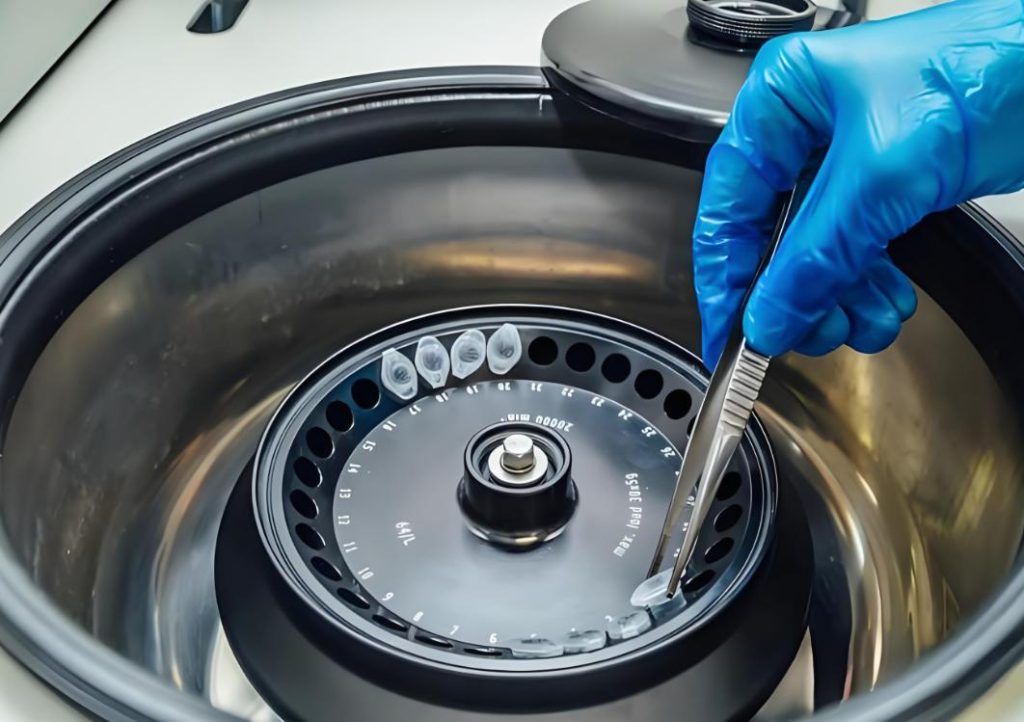

Rotor Type and Radius

The design and dimensions of the rotor significantly affect the centrifugal force and separation efficiency.

| Rotor Type | Radius Range (cm) | Applications | Efficiency |

| Fixed-angle | 5–15 | Rapid sedimentation (e.g., proteins) | High |

| Swing-out | 8–20 | Large-volume samples (e.g., blood bags) | Moderate |

| Near-vertical | 2–5 | Ultracentrifugation (e.g., DNA) | Very High |

Fixed-angle rotors enable faster separation due to shorter sedimentation paths, while swing-out rotors suit large volumes but require longer times. For instance, plasmid DNA isolation using a fixed-angle rotor at 20,000g takes 15 minutes, versus 30minutes for a swing-out rotor.

A larger rotor radius increases centrifugal force for a given RPM, enhancing separation efficiency. In cell pelleting applications, using a rotor with a longer radius resulted in clearer supernatant and reduced contamination.

Sample Properties

The physical and chemical properties of the sample play a crucial role in determining the success of centrifugation.

- Density: Denser particles sediment faster under centrifugal force. For example, in blood fractionation, red blood cells separate more quickly than plasma due to their higher density.

- Viscosity: High-viscosity samples, such as those containing polymers, require adjustments in speed and time to achieve optimal separation.

- Volume and Balance: Uneven sample distribution can create imbalance, risking equipment damage and compromising results.

Time

Duration must align with sedimentation kinetics. In differential centrifugation, nuclei (10–20 μm) pellet at 1,000g in 10 minutes, while ribosomes (20 nm) require 2 hours at 100,000g. Insufficient time causes co-sedimentation; excessive time risks thermal damage or energy waste.

Temperature

Temperature affects medium viscosity and biological activity:

- Low temperature(4°C): Minimizes enzymatic degradation (e.g., organelle isolation).

- Room temperature: Suitable for heat-resistant samples (e.g., genomic DNA). Studies show RNA extraction at 4°C improves yield by 30% by reducing RNase activity.

Many centrifuges offer temperature settings to prevent overheating during high-speed runs.

Medium Density

The density of the medium in which particles are suspended influences sedimentation.

Gradient Centrifugation: Using a density gradient medium, such as sucrose or cesium chloride, allows for finer separation of particles with minimal density differences.

In ultracentrifugation, cesium chloride gradients are commonly used for isolating viral DNA.

Practical Considerations and Optimization

Choosing the Right Parameters

Selecting appropriate centrifugation parameters is crucial for achieving desired results. Start by identifying the specific requirements of your experiment, such as the type of rotor, optimal speed, and temperature. For example, low-speed centrifuge (1,000-5,000 RPM) works well for cell separation, while high-speed or ultracentrifuge is better suited for isolating subcellular organelles or macromolecules. Always refer to manufacturer guidelines and experimental protocols to fine-tune these parameters for maximum efficiency.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Inefficiencies or errors during centrifugation can arise from several sources, such as imbalanced samples, rotor damage, or incorrect settings. Common issues include:

- Imbalance: Uneven loading of samples can lead to vibrations, equipment damage, or poor separation. Always balance tubes by weight, not just volume.

- Overheating: High-speed centrifugation can generate heat, affecting temperature-sensitive samples. Ensure the centrifuge’s cooling system is functional.

- Poor Separation: This may occur due to incorrect speed or insufficient time. Adjust parameters and repeat the process as necessary.

Regular maintenance and pre-run checks help mitigate these issues, ensuring reliable performance.

Safety Precautions

Operating centrifuges at high speeds involves potential risks, including mechanical failure or sample contamination. To ensure safety:

- Inspect Equipment: Check the rotor for cracks, corrosion, or wear before each use. Replace damaged components immediately.

- Use Appropriate Tubes: Select tubes rated for the required speed and temperature. Avoid overfilling, as this can cause spillage.

- Follow Protocols: Adhere to manufacturer instructions for loading, balancing, and operating the centrifuge. Always use the lid and safety locks.

- Emergency Protocols: Familiarize yourself with shutdown procedures and keep a safe distance during operation. In case of unusual noises or vibrations, stop the centrifuge immediately.

By carefully choosing parameters, troubleshooting effectively, and following safety measures, users can optimize centrifugation processes while minimizing risks and errors.

Centrifugation efficiency is governed by speed, rotor design, sample properties, time, temperature, and medium density. Practical optimization requires balancing particle characteristics (density, size) with experimental goals (speed, resolution, biocompatibility).